Making Assessment Personally Relevant

In my previous entry, I wrote,

I want my students to realize that learning is not about making your work conform to some standard imposed by the teacher. Learning is about creating your own standards and adjusting them based on your goals. Learning is about setting your own goals and monitoring your own progress. It is about having conversations with yourself and others.

My students have been very productive in the last couple of weeks and many of them seemed to have grasped the fact that learning is about conversations. Their Personal Progress Reports indicate that they have been reading other blogs and engaging in research that is personally relevant. Their words suggest that they have found topics that they are truly interested in exploring. They are developing their ideas and plans for further research.

My biggest challenge at this point is evaluation. Clay Burrell is right when he suggests in his comment that blogging and grading don't mix well. I agree. Nevertheless, as Clay observes, the students are "as addicted to being traditional students as we are to being traditional teachers." They are waiting for grades. They want to know what their work is worth. They have been trained, unfortunately, to equate learning with a letter or a percentage. It's not learning, in their view, it's not school, unless there's a grade attached.

So, how do I make them see that their ability to direct their own learning and engage in conversations with their peers is much more important than a formal grade?

Before I proceed, I should explain that my grade eight students are currently engaged in personal research projects on human rights and social justice. This project emerged from our literature units: we've read Animal Farm, and The Diary of a Young Girl. These two texts and their historical background helped us define a context within which the students are now operating as independent researchers. In other words, I gave them complete freedom to research any topic that fits into the context defined for us by the two texts and their inherent themes. The students are researching concentration camps, the Holocaust, child soldiers, euthanasia, current human rights abuses, the Rwandan genocide, the current situation in the Darfur region, children's rights, human trafficking, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Nazi propaganda posters and films, Fascism in Italy, war literature, Holocaust poetry, and many other topics.

Their first step involved locating appropriate resources and collecting information. After a while, the students' personal voices began to emerge and their personalities and individual interests began to dictate the direction of their research. I did not want to disrupt the process by marking their first entries and giving them a rubric with a grade on it. I believe that the act of assigning a grade is a very conclusive and definitive one. It means that whatever has been accomplished has been deemed to have certain value and that it is time to move on. I did not want my students to see their research as fragmented into a number of separate entries, punctuated by my rubrics and marks. I want them to see their work as one continuous flow, not a series of entries. So, I have refrained from assigning grades. Instead, I used class time to talk to them individually about their work and their ideas. I also commented on their work online. I shared resources, pointed out similarities between seemingly different projects, and did my best to encourage cognitive engagement.

Then, I decided to use Individual Progress Reports to help them keep track of their projects, reflect on the work already completed, and plan future direction of their research. As the progress reports of Alice, Gregory, and Amy clearly show, the Individual Progress Reports worked well. They gave my students an opportunity to think critically about their work. It also gave me an opportunity to have yet another conversation about their work, this time centered around a tangible artifact - their very own progress report.

Then, I realized that the students would also benefit from assigning value to their own work. Of course, the challenge with student self-evaluation is that many, when given an opportunity to give themselves a grade, are often too harsh on themselves. Others, on the other hand, sometimes choose not to take the task seriously and give themselves an A+. I realized that I needed to help them visualize their progress, their level of engagement, and their sense of ownership and not simply ask them to rate their own work using the traditional percentage or letter scale. Most importantly, I wanted them to see that an entry that contains lots of facts and links to many valuable resources is not necessarily as valuable as one that shows personal engagement with ideas, one where the readers can hear a unique, personal voice.

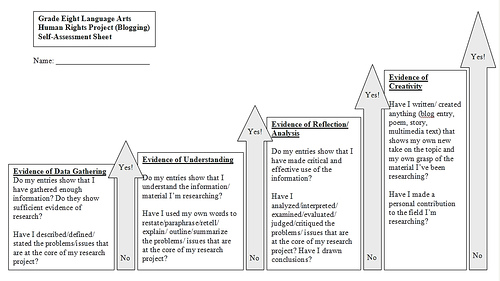

So, I created this Self-Evaluation Sheet to help my students plot their own progress:

So far, this handout has been a valuable tool. It gives my students an opportunity to look at their own work from the point of view of four distinct categories (there are, of course, echoes of Bloom here as well as Anderson and Krathwohl):

The first category, that of Data Gathering, asks them to check whether the key facts and issues pertaining to their independent research projects have been identified and posted: "Have I gathered enough information? Have I stated the facts at the core of my research project?"

Next, they have to ask themselves if their entries show that they have grasped the concepts they're researching. I refer to this stage as Evidence of Understanding. Have they used their own words to restate or paraphrase the material? Can they explain the key issues in their own words?

The third category pertains to analysis and reflection. In other words, I want the students to ask "So what?" What is the point of all this? What have I learned? What do I think about all the information that I've been reading and writing about?

The final category asks the students to think about Evidence of Creativity. I want them to ask themselves, "Have I made a personal and unique contribution as a researcher to the field that I'm exploring?"

Once we discussed the four categories, I asked them to draw a horizontal line inside each vertical arrow to represent their progress within each category: "You can place the line close to "No" if, in your opinion, you still have a lot of work to do in this category. You can draw the line somewhere around or even above "Yes" if you believe that your work already exhibits the attributes of this category. Be sure to place the line where it most accurately describes your progress."

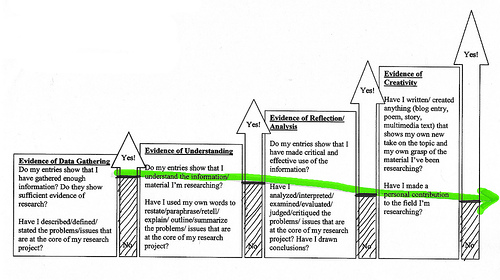

Once the students started plotting their efforts, many realized that their work has been following a flat line, or even falling:

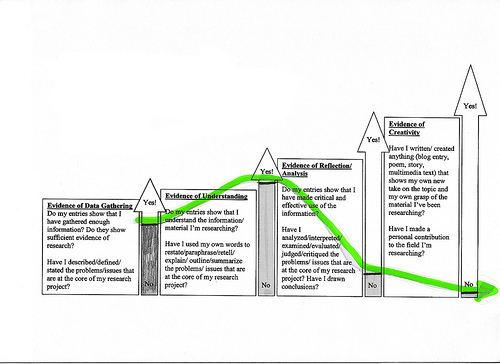

In some cases, the Self-Evaluation Sheet helped the students realize that they have not posted too many entries that indicated reflection or personal engagement and creativity:

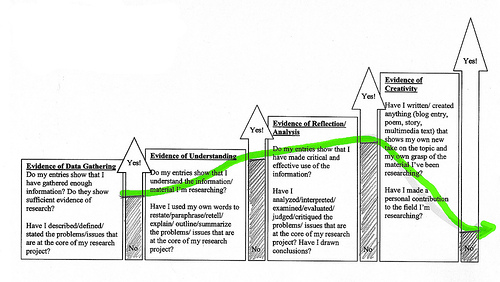

After a number of discussions about this chart, I was delighted to hear some students mention that without high achievement in the first three categories, it would be impossible to reach the top half of the arrow in the final category:

"You really can't do anything meaningful, like write a really good poem about your topic or do some multimedia stuff unless you've done all three first and really well, too."

"I think I need to go back and reflect on some of my entries. I have too many with just plain facts."

In other words, they seem to understand the relationship between all three categories and why each successive arrow is taller than the previous one. They understand that collecting information and putting it on their blog is not a challenging task. They understand that an entry that paraphrases information found online is not as interesting and valuable as one that shows the author in the process of analyzing and reflecting on his or her research. Finally, they can see and understand how much effort is needed to produce an entry that makes a personal statement, that constitutes a valuable and unique contribution to the studied field. In other words, they now understand that in order to produce something uniquely their own, they first need to have a solid grasp of all the facts and spend some time reflecting on them and their own thoughts about their research.

The most rewarding part of this experiment was when many students realized that some of their most often read (and commented upon) entries contain all of the first three categories: they contain facts, they paraphrase the information that the students have located, and they also contain a critical analysis and/or a reflection.

Needless to say, this experiment with student self-assessment and personal progress charts is a work in progress. I'm not sure if I'm going in the right direction. I'm not sure if refraining from formal evaluation until the very end of the project and until after the students have had a chance to critically assess and evaluate their own work is the right thing to do. However, so far the response from my students has been encouraging and I can see that the opportunity to plot and assess their progress has been much more valuable to them than a formal grade. If blogging at its best is really a conversation then we as educators are responsible for ensuring that these conversations are not defined by our rubrics but are guided instead by meaningful reflection.